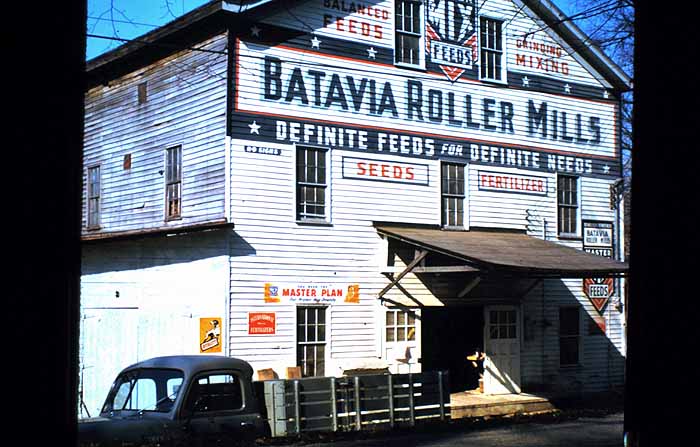

When my husband and I first moved to Batavia, I became fascinated with this old, wooden, 4-story abandoned wreck of a building I drove past regularly. It was wedged between the road and the river. Painted advertising was still visible on the front, labeling it Batavia Roller Mill, Definite Feeds for Definite Needs. I needed to know more.

I joined the Clermont County Historical Society, where I had access to good reference material. I found The History of Clermont County, 1880 by Louis Everts. It called the object of my interest Moore’s Mill, and said it is the oldest mill-site in Clermont County. In 1795 a millwright named Peter Wilson selected the site of Moore’s Mill as “affording the best water power on the East Fork.” 1795 was the first year that white settlers could live in this area legally.

It took a few years before George Ely, one of Batavia’s founders, built upon the site and used it to operate a small saw-mill.

In 1816, the property was purchased by Captain Charles Moore, a veteran of the War of 1812 from New Jersey. Soon after, he built a better sawmill, then added a small run of stones to grind corn. He built his family’s home across the road, and his house still stands.

In 1840, the Captain along with his sons Lindley Coates Moore and Charles Augustus Moore improved the mill yet again, building it into a three story frame building, supplied with turbine wheels and modern machinery. In its earliest life, it was powered by the falling of the East Fork when the river ran high. Later this was augmented by an auxiliary steam engine for times when the stream was low. Wheat flour and corn meal were its main product at this time. It was considered one of the best mills in the county. This building and operation stood for decades, up and running strong when the book was written.

But what happened to the mill after 1880? Further research brought me to an article written in The Clermont Sun in 1999 by Tom Fortney.

I learned that the four- story building standing is one that replaced that Moore’s Mill after it burned down. It had been owned by Teasdale and Moore until they sold it to John Orbaugh, owner of three other mills in the county. After Mr. Orbaugh went bankrupt he sold the mill to George Hugo. Mr. Hugo “had the gears humming during World War I, making corn meal for the U.S. government.” Afterward, he sold the mill to a pair of gentlemen named George Danby and Roscoe Tyler.

Mr. Danby and Mr. Tyler made further improvements to the mill, first changing the power source from part time water, to a full time tractor and then to a stationary gas engine.

These men hired William H. Henning to run the mill, since he had operated the mill during the war. In 1920, Mr. Henning bought it from Danby and Tyler. He improved the power one more time to electric.

William H. Henning operated the mill until his death in 1955, when his son Earl Henning took over the operation. As the county became more urbanized, the old mill changed from grinding wheat and corn meal to grinding and mixing animal feed. By 1961, that was no longer profitable and Earl Henning closed the mill for good.

Thereafter, there was some interest in converting the mill into a restaurant, or a nightclub, but lack of parking and sewerage made that impractical and the mill was left to deteriorate.

When I first saw the mill in the early 1980s, I peeked between the cracks in the siding, and extensive termite damage was evident. In a few years the roof started to fall in, and the mill’s ultimate demise was very rapid after that.

All that’s left of the mill is the picturesque but tumbling down stone foundation, and some rusting gears and machinery beneath the ivy. But I can imagine what had been, once upon a time.

I imagine there are still old houses in Batavia that have been built from wood milled here. I wonder how many hundreds of farmers in nearly a century and a half carted their corn and wheat harvest here. How many families were then fed with bread made from the grain? How many horses, cattle and hogs were raised on feed ground here? Many men worked here over time, swapping stories by the river with customers while the grinding wheels turned. The building is gone, but the spirit is still there. If you stand still and quiet on the riverbank you can imagine it all.

By Cindy Johnson